- Italian

- English

Dal successo con Verdone e I ragazzi della 3ª C alla vita accanto a Emanuele, il racconto di un padre che combatte ogni giorno con amore e coraggio.

Ha fatto ridere e sognare milioni di italiani negli anni ’80 e ’90, è stato l’usciere più famoso della televisione a Forum e ha calcato i palcoscenici di cinema e teatro. Ma oggi Fabrizio Bracconeri non parla di copioni o set: il suo vero ruolo è quello di padre, accanto al figlio Emanuele, affetto da autismo. Una vita fatta di sacrifici, di battaglie, ma anche di un amore che non si arrende mai. La sua voce non è più solo quella dell’attore che conoscevamo, ma quella di un uomo che racconta con sincerità la fatica e la bellezza di un amore assoluto. Ogni parola è un frammento di vita vissuta, ogni ricordo un tassello di una storia che è insieme personale e universale. Ho scelto di non interrompere questo flusso con filtri o mediazioni: lasciamo che sia lui, Fabrizio, a parlare.

E allora, partiamo dall’inizio.

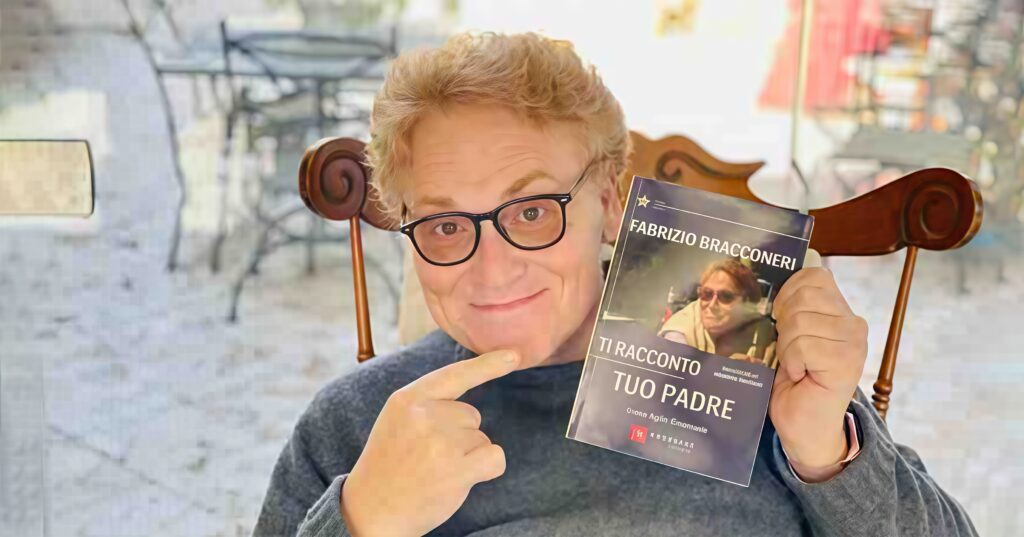

Partiamo dalla tua storia artistica: hai costruito la tua carriera tra teatro, cinema e televisione. Nel 2022 hai scritto un libro “ Ti racconto tuo padre. A mio figlio Emanuele “. Dove ti senti più a tuo agio? Dove ti senti più a tuo agio?

— A me piace tantissimo il contatto diretto con il pubblico, quindi il palco mi dà un’energia speciale, mi fa impazzire. Con il teatro mi sento davvero a casa, perché hai subito la risposta delle persone che hai davanti. Però devo dire che mi trovo bene anche in televisione e quando recito in un film. Andare al cinema come spettatore non mi entusiasma, ma girare un film sì: è un lavoro che mi piace. Credo che questo mestiere vada vissuto a 360 gradi, passando dal cinema alla televisione, dal teatro alla scrittura. Il libro, invece, è nato quasi per caso, senza che l’avessi programmato.

Dal cinema, con l’esordio accanto a Carlo Verdone in Acqua e sapone (1983), che ti valse anche la candidatura al Nastro d’Argento, fino al boom degli anni ’80 con film come Amarsi un po’ e soprattutto con il ruolo cult di Bruno Sacchi in I ragazzi della 3ª C (1987–1989), per poi arrivare a College nel 1990. Negli anni successivi sei tornato al cinema con pellicole come Gas (2005), Buona giornata (2012), Un santo senza parole (2015) e Lockdown all’italiana (2020), senza dimenticare il teatro e la lunga esperienza in televisione, da Forum a ItaliaSì!. Hai fatto davvero tanto: sei un artista completo.

Ti ringrazio per avermi definito artista e completo, perché in realtà io non mi sento mai artista. Mi sento una persona normale che fa questo lavoro, che mi piace e che porto avanti con passione e voglia. Devo dirti però la verità: adesso, a 61 anni, sono un po’ stanco. Non faccio più serate, anche per mio figlio che ormai ha 24 anni e va seguito, soprattutto nel fine settimana quando è a casa. E poi, naturalmente, l’età comincia a farsi sentire. Come dici giustamente tu, ho fatto tanto, e ora preferisco dedicarmi alla famiglia.

Restando sul tema della famiglia, parliamo del tuo libro Ti racconto tuo padre, nato come una lettera a tuo figlio Emanuele. Com’è stato trasformare sentimenti così intimi in pagine pubbliche?

— Voglio far capire alla gente che, se hai un problema del genere, ti puoi considerare fortunato se riesci a permetterti una persona che stia con te e ti aiuti ad assistere tuo figlio. O se puoi sostenere terapie private, perché qui non ti passa niente nessuno. Io mi sento fortunato, ma conosco tante famiglie che purtroppo non possono fare terapie, non possono avere quello che ho potuto fare io. Non c’è grande assistenza statale per questi ragazzi e con uno stipendio normale è veramente dura. Forse a 18 anni a qualcuno danno la pensione, ad altri no. C’è stato persino un periodo in cui sembrava che, compiuti i 18 anni, magicamente l’autismo sparisse di colpo e non ti riconoscevano nemmeno la pensione. È davvero faticoso per una famiglia che deve dedicare 24 ore su 24 ad accudire un figlio. Emanuele ha 24 anni, porta il pannolone, non parla, non mangia da solo, non si lascia toccare il viso per la barba: ogni volta diventa una violenza, servono tre o quattro persone per reggerlo. Io stesso gliela taglio, ma anche il barbiere fa fatica. È pericoloso, è pesante, ti porta via energie non solo fisiche ma anche mentali. Se devo andare a parlare con qualcuno, devo chiamare sempre qualcuno che possa stare con Emanuele, ovviamente pagando. Una famiglia normale come fa? Avere una persona che si occupi di Emanuele o di un bambino nelle sue condizioni costa, costa tanto. Faccio un esempio: se andiamo a mangiare una pizza io, mia moglie, tu e tuo marito, per me quella pizza non costa come a te. A me costa il doppio, perché oltre ai 25 euro della pizza devo pagare altre 30 euro l’ora a chi resta a casa con Emanuele. Perché lui non può venire al ristorante: non si siede, mangia un po’ poi si alza, vuole andare via, urla. Quindi serve sempre qualcuno che lo tenga per quelle due, tre, quattro ore. Ecco perché dico che è tutto molto più difficile.

C’è stata una reazione che ti ha colpito in modo particolare tra i lettori? Un commento, una recensione, o magari l’affetto di famiglie che vivono la tua stessa situazione?

—Guarda, quello che mi ha colpito di più sono state le persone che giudicano con facilitài. Frasi del tipo: “fa’ cinema che è meglio”, come se io avessi avuto la volontà di scrivere un bestseller. Non era quello il mio intento. Io non volevo scrivere un best seller: volevo semplicemente raccontare cosa può vivere una famiglia come la mia, affrontando il problema della disabilità. Non ho mai avuto la pretesa di essere un grande scrittore. Ho scritto come mi veniva, nel mio modo di essere, senza cercare voli pindarici o virtuosismi di stile. Ho fatto una cosa semplice, scritta col cuore, in maniera che tutti potessero capire, senza pretese, nemmeno economiche.

C’è un capitolo del libro che ti ha emozionato particolarmente quando lo hai riletto?

— Ti dico la verità: l’ho riletto una sola volta. Sì, mi emoziona, ma preferisco non rileggerlo perché rivivo cose che non voglio rivivere, soprattutto quando Emanuele era piccolo: le battaglie con le istituzioni, le tante lotte che ho fatto. Ricordarle mi dà molto nervosismo, anche perché penso sempre: “se mi avessero fatto questo, se avessi potuto avere quell’altro, magari oggi avrei ottenuto qualche risultato in più”. E questo mi porta a dare sempre la colpa a me stesso.

Sei sempre molto diretto nel raccontare le difficoltà delle famiglie con figli autistici. Cosa manca oggi in Italia per sostenere davvero questa realtà?

— Manca tutto, mancano le basi. Oggi ci si affida a cooperative o associazioni il cui scopo principale, purtroppo, è fare profitto: questa è la verità, nessuno fa niente per niente. Se io aprissi un’associazione o una cooperativa, dovrei comunque pagare le persone che ci lavorano e quindi i costi verrebbero scaricati sulle famiglie, che devono pagare le terapie per i ragazzi. A me piacerebbe che esistessero strutture pubbliche, come ci sono le scuole statali. Dovrebbero esserci veri e propri istituti medico-psico-pedagogici dedicati alla disabilità, perché non tutte le disabilità sono uguali. Servono luoghi che possano davvero aiutare i ragazzi e sostenere le famiglie e soprattutto nessun costo per le famiglie.

Parliamo dei costi delle terapie: quanto pesano realmente sulle famiglie?

— Parliamo di terapie che costano 35 euro l’ora, e che possono arrivare a 3.000 o 4.000 euro al mese, più 700 euro di pulmino. Mi chiedo come possa una famiglia, con un solo stipendio di 1.500 euro al mese, sostenere tutto questo. Le associazioni o le cooperative fanno aggregazione: tengono i ragazzi insieme, gli fanno fare qualche attività semplice, magari sporcarsi le mani sul tavolino. Per carità, serve, ma non è una vera terapia. È aggregazione, è tenerli tre ore in compagnia e permettere alla famiglia di respirare un po’. Perché noi una vita non ce l’abbiamo: se dobbiamo andare a fare la spesa, o ce lo portiamo dietro o non possiamo. Ti faccio un esempio: se vado al supermercato con mia moglie, lui non vuole scendere dalla macchina. Allora devo lasciarlo lì con l’aria condizionata e il motore acceso. E i posti per disabili? Sempre occupati da qualcuno che non ha il permesso. Queste sono battaglie che faccio tutte le settimane. Per fortuna abbiamo trovato un istituto che lo tiene la mattina dalle 8 alle 14: sono ore preziose, perché in quel tempo mia moglie può anche solo uscire a trovare un’amica e avere un minimo di vita sociale. Perché la verità è che, dopo due o tre volte che una persona viene a casa tua e si trova davanti questa situazione, con tuo figlio che ti gira intorno, ti tocca con le mani bagnate… anche gli amici alla fine si scocciano. E tu rimani sempre più solo.

Fabrizio, cosa ti senti di dire a un genitore che riceve per la prima volta, magari anche in modo brusco, la diagnosi: “tuo figlio è autistico”?

— Guarda, la diagnosi di autismo è difficile da affrontare. Spesso ci si accorge tardi, quando l’autismo è più pesante. E cosa posso dire? Che purtroppo la vita è segnata, ma bisogna combattere e non abbassare mai la testa.

Le famiglie che affrontano problemi gravi lo sanno: se il problema è superabile, è diverso. Io penso spesso che magari fosse stata la sindrome di Down: lì almeno puoi interagire, puoi parlare. Con Emanuele è diverso. Adesso, per esempio, è qui vicino a me sul divano: si alza, si siede, si rialza di nuovo… ma non sai se ti capisce davvero. Se lo chiamo, “Emanuele!”, a volte non si gira nemmeno.

Qual è il tuo più grande desiderio?

— Il mio più grande desiderio è sentirlo, un giorno, dire “papà” o “mamma”.

Qual è la forza che vi fa andare avanti in una situazione così pesante, non solo dal punto di vista umano ma anche nella gestione del quotidiano?

— La nostra forza è l’amore che io e mia moglie Monica abbiamo per Emanuele e l’idea di famiglia che ci siamo costruiti fin da quando ci siamo messi insieme. Sono 28 anni che stiamo insieme, non siamo più ai primi anni: abbiamo vissuto il problema e lo abbiamo affrontato. E ti dico la verità: io non riesco nemmeno a condannare quel padre o quella madre che, davanti a una situazione così, si tirano indietro, abbandonano la famiglia e dicono “basta, io mi tiro fuori”. Non li condanno, perché capisco che può essere un limite umano: non è per tutti.Noi, invece, abbiamo sempre interpretato Emanuele come un dono. Il Signore te lo manda perché tu sei in grado di gestirlo. Se lo avesse mandato a qualcun altro, magari sarebbe stato ingestibile e il malato stesso si sarebbe trovato in condizioni ancora più difficili.

Secondo te, cosa dovrebbe fare concretamente lo Stato italiano per aiutare le famiglie che vivono questa realtà?

— Partiamo da un presupposto: dieci anni fa in Italia fu istituito per la prima volta il Ministero della Disabilità, voluto fortemente dalla Lega. Poi il governo cadde e, con il nuovo assetto politico, la prima cosa che fecero fu toglierlo. Oggi, con il nuovo governo, è tornato e il ministro Locatelli, che conosco bene ed è una persona splendida, dedicata 24 ore su 24 a questi ragazzi, è stato rimesso al suo posto. Ma non può fare molto di più, perché manca il portafoglio, mancano i fondi. Ti faccio un esempio: il centro che frequenta Emanuele sarebbe più utile se lo Stato riconoscesse contributi economici diretti, così potrebbe crescere, accogliere più bambini, offrire più attività. In realtà, in ogni città, piccola o grande che sia, dovrebbe esserci una struttura del genere, accompagnarli in un percorso e portarli avanti, ma tutto a spese dello stato. La medicina oggi ha fatto molti passi avanti: non dico che si possa guarire, ma in alcuni casi si riesce a comunicare meglio, a rendere i ragazzi più indipendenti. Ecco, l’indipendenza è fondamentale. Mio figlio purtroppo non ce l’ha: porta il pannolone 24 ore su 24. Sapete cosa significa? Che non puoi andare a casa di nessuno, perché se fa i suoi bisogni lì diventa complicato, e parliamo di un ragazzo di 24 anni, non di un bambino. Ti ritrovi a vivere isolato: magari inviti gente a cena e succede qualcosa, oppure sei in macchina e lui bagna il sedile nuovo di qualcuno. Allora preferisci vivere da solo, comprarti una macchina sapendo che verrà distrutta. Io ne ho avuta una che Emanuele, nei momenti di nervosismo, addirittura mordeva la guarnizione tra vetro e sportello. Se sei alla guida, cosa fai? Non puoi fermarti in mezzo alla strada a dirgli “non mordere”. Così impari ad accettare anche questo: compri la macchina e sai già che sarà rovinata, che il sedile in pelle tra qualche settimana avrà buchi. Perché magari vai a fare la spesa e, in dieci minuti in cui resta in auto, ha già dato morsi al sedile. Questa è la realtà. Lo Stato dovrebbe capirlo e creare strutture serie, non lasciare tutto sulle spalle delle famiglie.

C’è stato un momento in cui tu e tua moglie avete pensato: “non ce la facciamo più”?

— Succede, ma non è un “non ce la faccio più” riferito a Emanuele. È piuttosto il non farcela più a reggere il nostro nervosismo. Ti faccio un esempio: io oggi sono tornato da Roma, dove ero per lavoro. Mia moglie invece ha passato tutta la giornata con Emanuele, e questo ti distrugge. Io a Roma, tra una cena, un incontro con persone, un po’ di musica, mi sono distratto; lei no. Queste sono cose difficili da capire per chi non vive una situazione simile. Io lo dicevo sempre anche quando ero a Forum: finché c’è la lucetta rossa della telecamera accesa, tutti ti dicono “hai ragione”. Ma quando la lucetta si spegne, il problema rimane a chi ce l’ha davvero. Anche questa intervista: chi la leggerà magari penserà “sì, è vero, è così”, ma poi, girata la pagina, per loro finisce lì. Invece il problema rimane a me, a mia moglie, e a tutte le famiglie che vivono questa realtà.

Quali sono i tuoi prossimi progetti lavorativi?

— Se tutto va come deve andare, da settembre avrò una rubrica in un programma Rai dove parleremo di disabilità, grazie a Pierluigi Diaco, che è una persona eccezionale. Sono stato ospite a BellaMa’ e mi ha detto: “Guarda, io voglio fare una rubrica così, perché conosco bene la tua situazione e la tua famiglia, e voglio affidarla a te”. Parleremo di società e, in particolare, di disabilità. Però parliamo sempre di televisione: se la rubrica funziona e viene seguita andrà avanti, altrimenti no. La televisione si fa con i numeri, con la pubblicità, e c’è poco da fare: i numeri sono numeri. Purtroppo la gente preferisce ascoltare gossip, scandali, tradimenti, piuttosto che affrontare i problemi concreti del Paese, che invece avrebbero bisogno di soluzioni. E non parlo solo di disabilità: in Italia ci sono migliaia di problemi, quasi tutti risolvibili, ma la gente preferisce distrarsi con altro. È naturale: ognuno ha già i propri problemi, pagare luce, gas, spazzatura, spesa. Ci sono famiglie che, oltre a tutte queste difficoltà, hanno anche la disabilità in casa. Ed è bene ricordarlo: prima o poi, tutti diventeremo disabili con l’età.

Un’ultima domanda, poi ti lascio a Emanuele: sei felice, Fabrizio?

— Siamo felici, perché fortunatamente ho fatto e faccio un lavoro che mi ha reso, tra virgolette, più fortunato di altri dal punto di vista economico. Però la felicità… diciamo che ci sono giorni sì e giorni no. Sono felice perché ho altri tre figli, normodotati, e tre nipoti che adoro. Ma, vivendo lontani, li vedo poco, e questo mi manca molto. La felicità per me è fatta di attimi: sono felice quando vado a pesca, ma basta una telefonata di mia moglie “guarda che a Emanuele è venuta una crisi epilettica” e in un attimo è finita. Lascio lì le canne e corro a casa. La felicità bisogna costruirsela, cercarsela: vale per tutti. A volte basta una giornata tranquilla a casa con Emanuele, quando è sereno, o la visita di qualche amico che conosce bene la nostra situazione e non si lascia spaventare. Ho degli amici, Fabrizio e Dina, che ci aprono la loro casa e ci fanno sentire a nostro agio. Emanuele lì si muove liberamente, perché c’è spazio e non si sente braccato. In case più piccole invece si innervosisce, vuole uscire, e allora spesso preferiamo restare a casa nostra per evitare situazioni difficili. Ci tengo però a dirti una cosa: il merito è soprattutto di mia moglie. Lei combatte come una leonessa, 24 ore su 24. Io con il lavoro spesso sono fuori, mi distraggo, magari sto tre giorni a Roma; lei invece rimane qui in Sicilia, in una casa grande sì, adattata ad Emanuele, ma comunque isolata. Emanuele urla, vuole uscire in giardino, e lei affronta tutto questo ogni giorno. È una vita di sacrifici, e non tutti possono permettersi un aiuto esterno: una persona che ti assista costa 35 euro l’ora. Quindi, se oggi andiamo avanti, gran parte del merito è suo.

Fabrizio Bracconeri è un padre che vive ogni giorno come una battaglia d’amore. Il suo sogno più grande non è un nuovo ruolo o un palcoscenico, ma una sola parola: “papà”. E a voi lettori resta un compito: non voltare pagina, non dimenticare.

From his success with Verdone and I ragazzi della 3ª C to life alongside his son Emanuele, this is the story of a father who fights every day with love and courage.

He made millions of Italians laugh and dream in the ’80s and ’90s, he was the most famous usher on Italian television in Forum, and he has walked the stages of cinema and theatre. But today Fabrizio Bracconeri no longer speaks about scripts or sets: his true role is that of a father, alongside his son Emanuele, who has autism. A life made of sacrifices, battles, but also of a love that never surrenders.

His voice is no longer just that of the actor we once knew, but that of a man who tells with honesty the fatigue and the beauty of absolute love. Every word is a fragment of lived life, every memory a piece of a story that is both personal and universal. I chose not to interrupt this flow with filters or mediations: let Fabrizio speak for himself.

And so, let’s start from the beginning.

Let’s start with your artistic journey: you’ve built a career across theatre, cinema, and television. In 2022, you also wrote a book, Ti racconto tuo padre. A mio figlio Emanuele.

Let’s start with your artistic journey: you’ve built a career across theatre, cinema, and television. In 2022, you also wrote a book, Ti racconto tuo padre. A mio figlio Emanuele. Where do you feel most at home?

— I love direct contact with the audience, so the stage gives me a special energy, it drives me crazy. With theatre, I really feel at home, because you get an immediate response from the people in front of you. But I also feel good on television and when acting in films. Going to the cinema as a spectator doesn’t excite me much, but shooting a film does: it’s work I enjoy. I believe this profession should be lived at 360 degrees, moving between cinema, television, theatre, and even writing. The book, instead, was born almost by accident, without planning it.

From cinema, with your debut alongside Carlo Verdone in Acqua e sapone (1983) which earned you a Nastro d’Argento nomination through the boom of the ’80s with films like Amarsi un po’ and, above all, the cult role of Bruno Sacchi in I ragazzi della 3ª C (1987–1989), then College in 1990. In later years you returned to film with titles like Gas (2005), Buona giornata (2012), Un santo senza parole (2015) and Lockdown all’italiana (2020), without forgetting theatre and your long TV experience, from Forum to ItaliaSì!. You really have done a lot: you’re a complete artist.

Thank you for calling me an artist and “complete,” because in truth, I never feel like an artist. I just feel like a normal person who does this job, which I enjoy and carry out with passion and dedication. But to tell you the truth, at 61 I’m a bit tired. I don’t do evening shows anymore, partly because of my son who is now 24 and needs to be followed, especially on weekends when he’s at home. And of course, age is starting to show. As you rightly said, I’ve done a lot, and now I prefer to dedicate myself to my family.

Staying on the theme of family, let’s talk about your book Ti racconto tuo padre, which was born as a letter to your son Emanuele. How was it to transform such intimate feelings into public pages?

— I wanted people to understand that if you face a situation like this, you’re lucky if you can afford someone to help you, to be with your child. Or if you can pay for private therapy, because here nobody gives you anything. I feel lucky, but I know many families who unfortunately can’t afford therapy, who can’t have what I was able to provide. There isn’t much state support for these kids, and with a normal salary it’s really hard.

Sometimes, when children turn 18, some families are granted a pension, others not. There was even a period when it seemed that at 18 autism magically disappeared overnight, and they would stop recognizing the pension. It’s truly exhausting for a family that must dedicate 24 hours a day to caring for a child.

Emanuele is 24, he wears diapers, he doesn’t speak, he doesn’t eat on his own, he won’t let anyone touch his face for shaving. It becomes a struggle every time, and it takes three or four people to hold him still. I do it myself, but even the barber struggles. It’s dangerous, it’s heavy, it drains not only your physical energy but also your mental strength.

If I have to go meet someone, I always have to call someone to stay with Emanuele, obviously paying them. How does a normal family cope? Having someone look after Emanuele or a child in similar conditions costs a lot.

For example: if we go out for pizza, for me it costs double what it costs you. If you and your husband pay €25 for dinner, I pay that plus another €30 an hour for the person who stays home with Emanuele. Because he can’t come with us: he won’t sit down, he eats a little and then gets up, wants to leave, screams. That’s why I say: everything is more difficult.

Has there been a reaction from readers that struck you in particular? A comment, a review, or the affection of families sharing your situation?

— What struck me most were the people who judge so easily. Comments like: “Stick to cinema, it’s better.” As if I had wanted to write a bestseller. That was never my intention.

I didn’t want to write a bestseller, I simply wanted to tell what a family like mine goes through when facing disability. I never claimed to be a great writer. I wrote the way I felt, in my own way, without stylistic flights of fancy. I just wrote something simple, written with my heart, in a way that everyone could understand, without any pretensions, not even financial ones.

Was there a chapter in the book that particularly moved you when you reread it?

Honestly, I only reread it once. Yes, it moves me, but I prefer not to reread it because it makes me relive things I don’t want to relive especially when Emanuele was little: the battles with institutions, the many struggles I fought. Remembering them makes me very nervous, because I always think: “If only they had given me this, if only I had been able to do that, maybe today things would be different.” And that always makes me blame myself.

You’re very direct in describing the struggles of families with autistic children. What’s missing in Italy today to truly support them?

— Everything is missing the foundations themselves. Today it all falls on cooperatives or associations whose main goal, unfortunately, is profit. That’s the truth: nobody does anything for nothing.

If I opened an association, of course I’d have to pay the people working there, so families would still bear the costs. Instead, I’d like there to be public structures, like state schools, but dedicated to disability: proper medical-psycho-pedagogical institutions. Because not all disabilities are the same. We need places that can really help the kids and support families and at no cost to them.

Let’s talk about therapy costs: how much do they really weigh on families?

— We’re talking about therapy at €35 per hour, which can add up to €3,000 or €4,000 per month, plus €700 for transport. How can a family living on one salary of €1,500 a month possibly sustain that?

Associations and cooperatives offer aggregation: they keep the kids together, make them do small activities, maybe get their hands dirty with paint at a table. Sure, it helps, but it’s not therapy. It’s just aggregation, three hours of company, giving the family a chance to breathe.

Because we don’t really have a life. If we need groceries, either we take him with us or we don’t go. For example: when I go shopping with my wife, Emanuele doesn’t want to get out of the car. So I have to leave him inside, with the engine and the AC running. And the disabled parking spaces? Always occupied by someone without a permit. These are the weekly battles I fight.

Luckily, we found an institution that looks after him from 8 AM to 2 PM. Those are precious hours: my wife can finally go out, see a friend, and have a little social life. Otherwise, we have none. Because after two or three visits, even friends get tired of coming to our house, seeing the situation, being touched by Emanuele with wet hands… people eventually stop coming. And you’re left more and more alone.

Fabrizio, what would you say to a parent who receives, perhaps brutally, the diagnosis: “your child is autistic”?

— The diagnosis of autism is very hard. Often people don’t notice until the autism is severe. And what can I say? Unfortunately, life is marked but you must fight and never bow your head.

Families dealing with serious conditions know this: if the problem is manageable, it’s different. I often think: if only my son had Down syndrome, at least you can interact, you can talk. With Emanuele it’s different.

For example, right now he’s sitting next to me on the couch: he stands up, sits down, stands up again… but you don’t know if he truly understands you. If I call him “Emanuele!”—sometimes he doesn’t even turn around.

What is your greatest wish?

— My greatest wish is to one day hear him say “dad” or “mom.”

What gives you and your wife the strength to keep going in such a heavy situation, both emotionally and in daily life?

— Our strength is the love that my wife Monica and I have for Emanuele, and the idea of family we built when we first got together. We’ve been together for 28 years; it’s not the early days anymore. We’ve lived through this problem and faced it head-on.

And I’ll tell you honestly: I can’t even condemn those fathers or mothers who, faced with such a situation, give up, abandon their families, and say “I can’t do this anymore.” I can’t judge them, because I understand it can be a human limit not everyone can handle it.

We, instead, have always seen Emanuele as a gift. God gave him to us because we were capable of caring for him. If He had given him to someone else, maybe it would have been unmanageable, and the child would have been left in even worse conditions.

In your view, what should the Italian state concretely do to help families living this reality?

— Let’s start from the beginning: ten years ago Italy established, for the first time, a Ministry of Disability, strongly pushed by the Lega party. Then the government fell, and the first thing the new coalition did was abolish it.

Now, with the new government, it has been reinstated, with Minister Locatelli whom I know well, a wonderful person dedicated 24 hours a day to these kids. But even he can’t do much more, because there’s no budget.

Take the center that Emanuele attends: it would be far more useful if the state provided direct funding, so it could grow, welcome more children, and offer more activities.

In reality, every city, large or small, should have such a structure, accompanying kids along a path and supporting families, with everything covered by the state.

Medicine has advanced a lot: I don’t say autism can be cured, but in some cases, communication improves, independence grows. Independence is key.

My son, unfortunately, doesn’t have it: he wears diapers 24 hours a day. Do you know what that means? That you can’t go to anyone’s house. Imagine: he’s 24, not a child. If he soils himself in someone’s home, it’s complicated. Or if we invite people over for dinner and it happens, Emanuele walks around the house it’s awkward.

Even cars: I had one that Emanuele chewed on when he was nervous. He would bite the rubber seals of the door. If you’re driving, what do you do? You can’t stop in the middle of the road and tell him “don’t bite.” So you buy a car already knowing it’ll get destroyed. Leather seats? Within weeks, there are holes. That’s reality.

The state needs to understand this and create serious structures, instead of leaving everything on families’ shoulders.

Was there ever a moment when you and your wife thought: “We can’t do this anymore”?

— It happens but it’s never a “we can’t do this anymore” about Emanuele. It’s about not being able to handle our own exhaustion.

For example: today I came back from Rome, where I was working. My wife, meanwhile, spent the whole day with Emanuele and that drains you.

In Rome, between dinner, meeting people, and a bit of music, I got some distraction. She didn’t.

These are things hard for “normal” people to understand. I used to say it even on Forum: while the red light of the camera is on, everyone agrees with you, “yes, you’re right.” But when the light goes off, the problem remains with those who actually live it.

Even in this interview: people will read it and say, “yes, it’s true, it’s tough” but after they turn the page, it’s over. The problem remains with me, with my wife, and with all the families living this.

What are your upcoming projects?

— If everything goes as planned, starting in September I’ll have a segment on a Rai program where we’ll talk about disability, thanks to Pierluigi Diaco, who is an exceptional person.

I was a guest on BellaMa’ and he told me: “Look, I want to create a segment like this, because I know your situation and your family well, and I want you to lead it.”

We’ll talk about society and disability. But of course, this is still television: if the segment works and gets viewers, it will continue. Otherwise, it won’t.

Television runs on numbers on ratings and advertising. And unfortunately, people prefer gossip, scandals, affairs, instead of listening to real problems that could actually be solved.

And I’m not just talking about disability: Italy has thousands of problems, many of them solvable. But people want distractions. They already have their own worries: paying electricity, gas, waste, groceries. And then there are families who, on top of all that, also have disabilities at home.

And let’s remember: sooner or later, with old age, we all become disabled.

One last question, then I’ll let you get back to Emanuele: Fabrizio, are you happy?

— We are happy, because fortunately I’ve done and still do work that has made me, relatively speaking, luckier than others financially.

But happiness… let’s say it comes and goes.

I’m happy because I have three other children, all without disabilities, and three grandchildren I adore. But since we live far apart, I don’t see them much and I miss them.

For me, happiness is made of moments: I’m happy when I go fishing. But then my wife calls “Emanuele just had an epileptic seizure” and in an instant, it’s over. I leave the fishing rods behind and rush home.

Happiness has to be built, searched for, that’s true for everyone.

Sometimes it’s just a peaceful day at home with Emanuele when he’s calm, or the visit of a friend who knows our situation well and isn’t scared off.

I have friends, Fabrizio and Dina, who open their home to us and make us feel comfortable. Emanuele moves freely there because there’s space he doesn’t feel cornered. In smaller houses, he gets anxious, wants to leave, so we often stay home to avoid problems.

But let me tell you this: most of the credit goes to my wife. She fights like a lioness, 24/7.

I, with my work, am often away. I get distracted, maybe spend three days in Rome. She, instead, stays here in Sicily, in a large house adapted for Emanuele, but still isolated. He screams, he wants to go outside, and she faces it every single day.

It’s a life of sacrifice, and not everyone can afford external help. An assistant costs €35 an hour. So if we’re still standing today, it’s thanks above all to her.

Fabrizio Bracconeri is a father who lives each day as a battle of love. His greatest dream is not a new role or a stage, but a single word: “dad.” And for you readers, one task remains: don’t turn the page, don’t forget.

By author